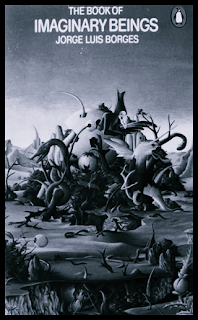

Some readers may look back with a certain fondness upon their youthful pastimes, such as the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, which allowed players to imagine an existence in a sword-and-sorcery setting under the controlling eye of a “dungeon master”, fighting all manner of impossible creatures in a hunt for treasure, weapons and spell books. Armed only with pencil, paper, dice of assorted geometries and a lead figurine marking the player’s position on the hexagonal chart paper of the dungeon, tens of thousands of teens and young adults shared in the common experience. Most important of all was the list of recommended reading that appeared in the introductory game modules, which served to introduce players to a number of written works – not just Tolkien and R.E. Howard, but older works such as Amadís de Gaula (the late medieval “book of chivalry”) and most importantly, The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges.

Click here to enlarge top photo.

Inspired by the bestiaries of old, Borges – one of the leading authors of the 20th century – included creatures from different cultures and times, including fictitious beasts such as a reptile imagined by C.S. Lewis for Perelandra (second volume of his “Space Trilogy”). This illustrated collection of fanciful creatures included some with powerful roots in historic tradition, such as the Golem.

“The cabbalists,” wrote Borges, “sought the secret of the creation of organic beings in the sacred texts. It was said demons could create large and solid creatures like the camel, but not fine and delicate ones, and Rabbi Eliezer denied them the ability to create anything smaller in size than a grain of barley. Golem was the name given to the man created by a combination of letters. The word literally means amorphous or inert matter.” He then goes on to cite Austrian writer Gustav Meyrink, author of Der Golem (1915): “The origin of the story goes back to the 17th century. According to lost Kabbalistic formulas, a rabbi created an artificial man – called the Golem – to ring the bells of the synagogue and engage in hard labor. He was not a man like others, and was motivated by a shallow and vegetative life. He endured until night, and owed his virtue to the power of a magical text place behind its teeth, attracting the free energies of the universe. One evening, before prayer, the rabbi forgot to remove the seal from the Golem’s mouth and the creature fell into a frenzied state, running down the darkened alleys, smashing all those who stood before it. The rabbi ultimately managed to tackle it and shatter the seal that animated it. The creature fell to the ground, leaving nothing more than the squalid clay figure that is still visible today in the Prague synagogue.”

Was the great Argentinean writer, poet, translator and critic aware of certain facts that led him to include this figure among the denizens of his Book of Imaginary Beings?

Guillermo Barrantes and Victor Coviello, authors of Buenos Aires es Leyenda, include in their compendium of the urban folklore of the Argentinean capital the strange story of the Gigante de Once (the Once Giant), a three-meter (9.8 ft.) tall entity reported by the residents of the city’s Balvanera district. The towering presence, however, was seen as a guardian angel of sorts, keeping a watchful eye on every street and alleyway. Local residents interviewed for the project agreed that there was a belief in a gentle giant as tall as a tree, walking in slow motion, fighting crime much like a superhero. A student from the Colegio San José is reported as saying: “One of my classmates says his uncle was saved by a three meter tall giant. He crashed his car, and the giant pulled him out before the vehicle exploded.”

Mystified, Barrantes and Coviello conducted an exhaustive search of documentary sources in the hopes of establishing a provenance to this legend. A report from 1930 mentioned the presence of a “giant figure removing debris” after the destruction of a confectionary shop during urban violence. Another source mentioned the arrival of a rabbi in Buenos Aires in the year 1900, either with his own Golem or the ability to create one. The whereabouts of this creation, after the rabbi’s passing, are also the subject of controversy: “According to some documents, it is said that the rabbi locked the monster in a room that cannot be entered. Some believe this room to be located in an annex of the Hospital Francés in the Caballito district. The hospital was built without this enclosure having ever been touched.”

A 1916 text by one Mascimiano Funes (a fascinating name, bearing in mind that “Funes the Memorious” is one of J.L. Borges’s better known short stories) advises: “There is an alleyway that cannot be seen, except from a balcony no one can reach, and this hidden alleyway is the dwelling place of He-Who-Was-Not-Born-of-a-Mother, the forsaken giant, who wanders aimlessly in that place, waiting, waiting…”

Leaving no stone unturned, the authors of Buenos Aires es Leyenda came across another compelling lead. In the early 1890s, Maria Salomé Loredo, a healer and seeress, had turned her home in the Balvanera district into a temple where she could receive her thousands of followers. Some suggest that there was a connection between the healer and the enigmatic rabbi with the Golem, the latter having shared Kabbalistic secrets with her that represented the wellspring of her curative abilities. The creature remained in her care after the rabbi’s passing, and was seen for the last time at María Loredo’s funeral in 1928, when a tall, slow-walking man was seen to make his way to her coffin, place a hand on it, and mutter a few words. “Some stories identify the mysterious visitor with the Golem itself, which had come to say farewell to his last mistress before walking away along the streets of Once, destined to wander them for eternity.”

Vampires: Fact, Fiction and Hearsay

The traditional image of the vampire – castle, expensive attire, medals and casket – is not readily associated with the Spanish-speaking Americas, although it figured prominently in a number of horror movie productions, usually involving Bram Stoker’s Count Dracula or his descendants having made the journey across the Atlantic for unspecified reasons that are not important to the plot.

Mexico, perhaps, can boast of having seminal cultures that turned vampires into gods – among the most fearsome in any pantheon of the Americas. The Mayan god Camatzotz (“death bat”) was a terrifying entity sent down from the sky to behead the second race of men, created out of wood, since their condition did not allow them to venerate their deities. Worship of this bat-god spread throughout Mesoamerica, leading some to suggest that the giant vampire bat (Desmodus draculae) of the Pleistocene may have survived into historic times, prompting humans to consider it a deity to be feared and appeased. The goddesses collectively known as Cihuateteo also had vampiric qualities, wandering the night and attacking children, having themselves died in childbirth.

But not all such entities can be consigned to the safety of myth and legend.

A story has been making the rounds of the Mexican paranormal world for many years now. Efforts at finding its putative source (a radio broadcast from the early 2000s) have been fruitless, so it should be classified as hearsay or the ultimate FOAFtale. Nonetheless, it is sufficiently compelling to include in this essay on high strangeness and improbable entities.

A nurse phoned a Mexican radio call-in show to describe – with considerable trepidation – an incident that allegedly occurred in 1977 at a very specific location: The Hospital Civil de Guadalajara’s specialized medicine unit. While workmen took their sledgehammers to a wall as part of a remodeling project, they were shocked beyond belief to see the old masonry crumble to dust, only to reveal the body of a woman immured since the colonial period of Mexican history, judging by her heavy and costly garments.

Legends about “emparedados” (a word currently for sandwiches, but employed in the 16th century for the cruel practice of burying victims behind walls, literally walling them in while alive) are common in the chronicles of Viceregal-age Mexico. In such stories an old wall crumbles by design or accident to reveal the skeleton of a family member punished for disgracing the family or a number of other reasons. It has also proven a popular fictional device in classic works of literature such as The Cask of Amontillado by Edgar Allan Poe. The difference in this case is that the immured woman was apparently alive.

Stretching the limits of credulity to their most threadbare, the nurse said the woman’s body was free of any corruption, perfectly preserved in a glass case. The laborers and their foreman were shocked beyond belief, as were physicians and nurses who flocked to see the phenomenon – but their amazement and even cries of “¡milagro!” (a miracle) that may have briefly filled the air were stifled by the fact that an adorned wooden cross had been driven into the woman’s heart.

No specifics are given, but the physicians must have opened the glass case and actually touched the body, as the nurse added that the immured woman’s eyelids were raised for inspection and she had “intense blue eyes.”

Rather than contacting the authorities – continued the nurse – the hospital staff called in clerics, believing that the woman was a vampiresa. Church authorities reported to the hospital, workers placed the body into a wooden casket and “wrapped the body in tinfoil” (probably Mylar) and took it away. Medical students and doctors alike were enjoined not to discuss the matter, threatened with the loss of their professional credentials. The nurse waited twenty years before speaking publicly, closing her astonishing tale by saying “the incorrupt body had been sent to the Vatican under Papal instructions.”

The only other bit of tangible information was that Dr. Mario Rivas Souza of SEMEFO (Servicio Médico Forense, the Mexican medical examiners’ unit) had been a party to the mind-bending event, having been the senior administrator who dealt with the four clergymen sent to handle the situation. A search reveals that Dr. Rivas was in fact affiliated with that clinical branch at the time of the alleged event, but had not practiced medicine at the hospital since the 1960s. Further sleuthing suggests that the event – if there is any truth to it – would have occurred not in the gleaming tower of the Hospital Civil de Gualajara but in the “Hospital Civil Viejo Fray Antonio Alcalde” – the single story building on Coronel Calderón street, whose construction began in the year 1788 and completed in 1794, adding another solid detail to the incredible story.

Nor is this the only sample of vampire lore coming out of Guadalajara: the narrative of the vampire buried under a tree in the city’s Panteón de Belén cemetery is widely known and has acquired international standing.

For a more tangible Latin American vampire story we must go to Perú, where the citizens of Pisco are split between veneration and fear over a tomb in the city’s old Beneficiencia Pública cemetery. It houses the remains of Sarah Ellen, a migrant to South America who died over a hundred and fifty years ago. The place housing her mortal remains became notorious when it was among the few structures in the cemetery not levelled by a 7.9 earthquake in 2007.

Part II in this series continues tomorrow Saturday, February 22, 2014.